Institutional Performance Management

Move forward with precision

Drive enrollment & retention, manage expenses, and improve learning outcomes. HelioCampus helps you navigate today's high stakes with AI-ready Data Analytics, Financial Intelligence tools, and a robust Assessment & Credentialing platform.

Trusted By

.png)

Unlocking insights with Institutional Performance Management

HelioCampus helps higher education institutions see, set, and track actionable opportunities for continuous improvement using Institutional Performance Management tools and practices. We partner with you to optimize your data infrastructure, implement AI-powered models, automate manual workflows, and evaluate investments to bring your strategic mission to life.

Data Analytics

Empower campus leaders to ensure student success, accelerate decision-making, and optimize operational processes with a secure data platform that helps you uncover actionable insights from across the student lifecycle. Plus the HelioCampus secret sauce - our data science and analytics services, which include proven machine learning and AI models - help you and your team build data fluency, drive change, and advance analytics priorities on your campus.

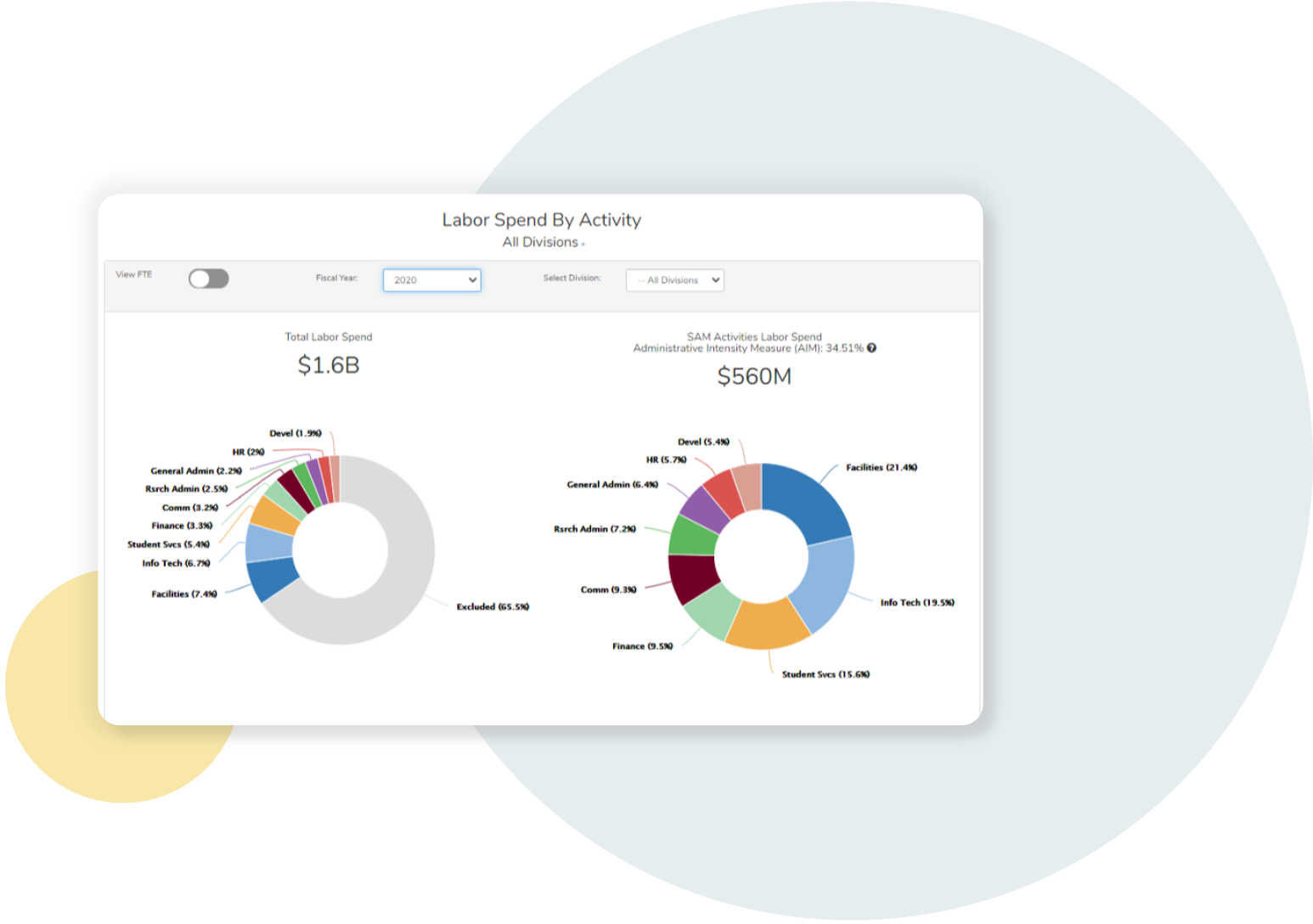

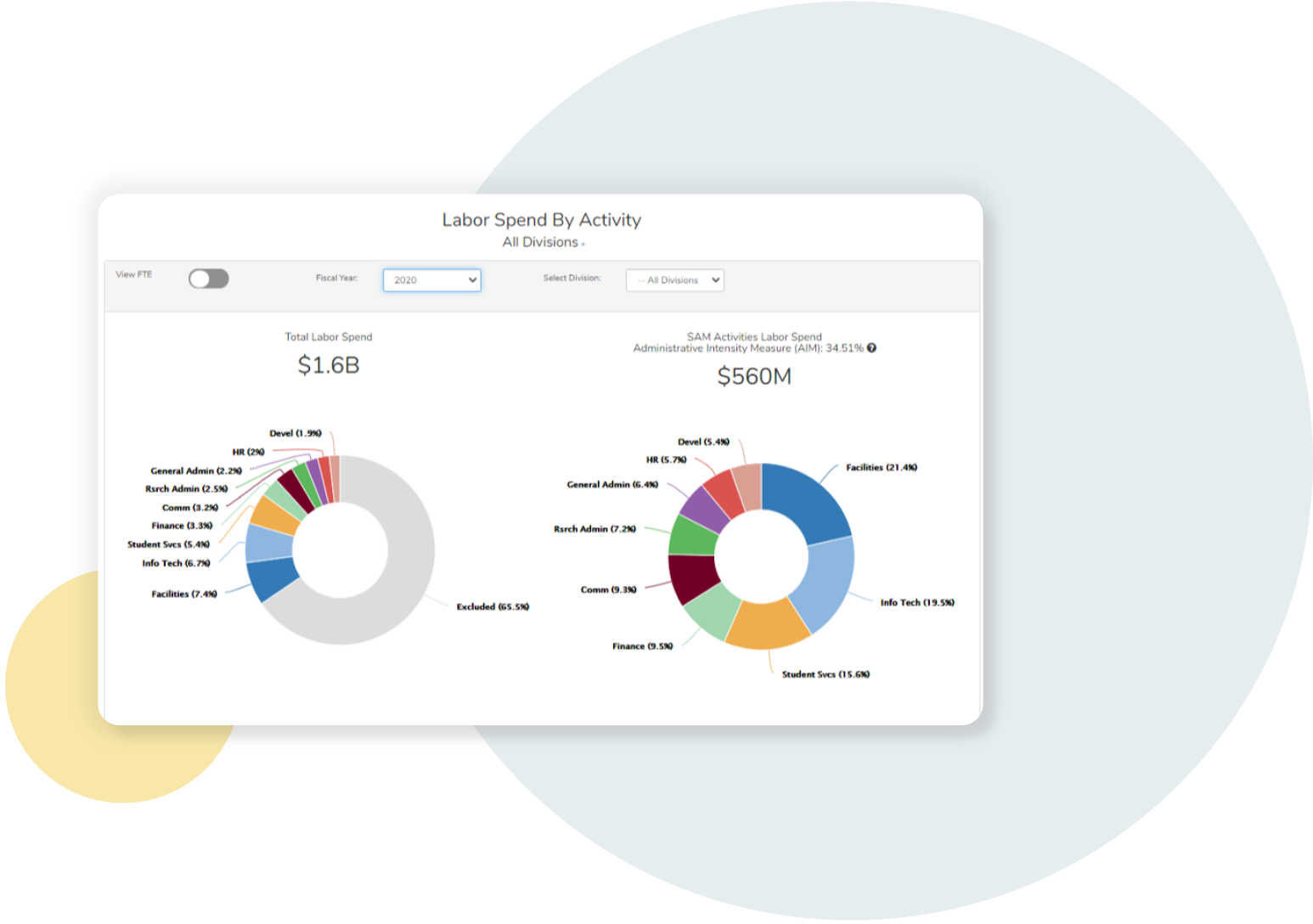

Financial Intelligence

Get deep financial insights to power essential administrative operations like annual budgeting, workforce planning, and financial sustainability efforts. Only HelioCampus offers higher ed finance and operations leaders access to benchmarked labor data and a finance community of practice to help you plan for a variety of scenarios, understand the direct cost of instruction, mitigate risks, and chart a financial path to their mission.

Explore Financial Intelligence

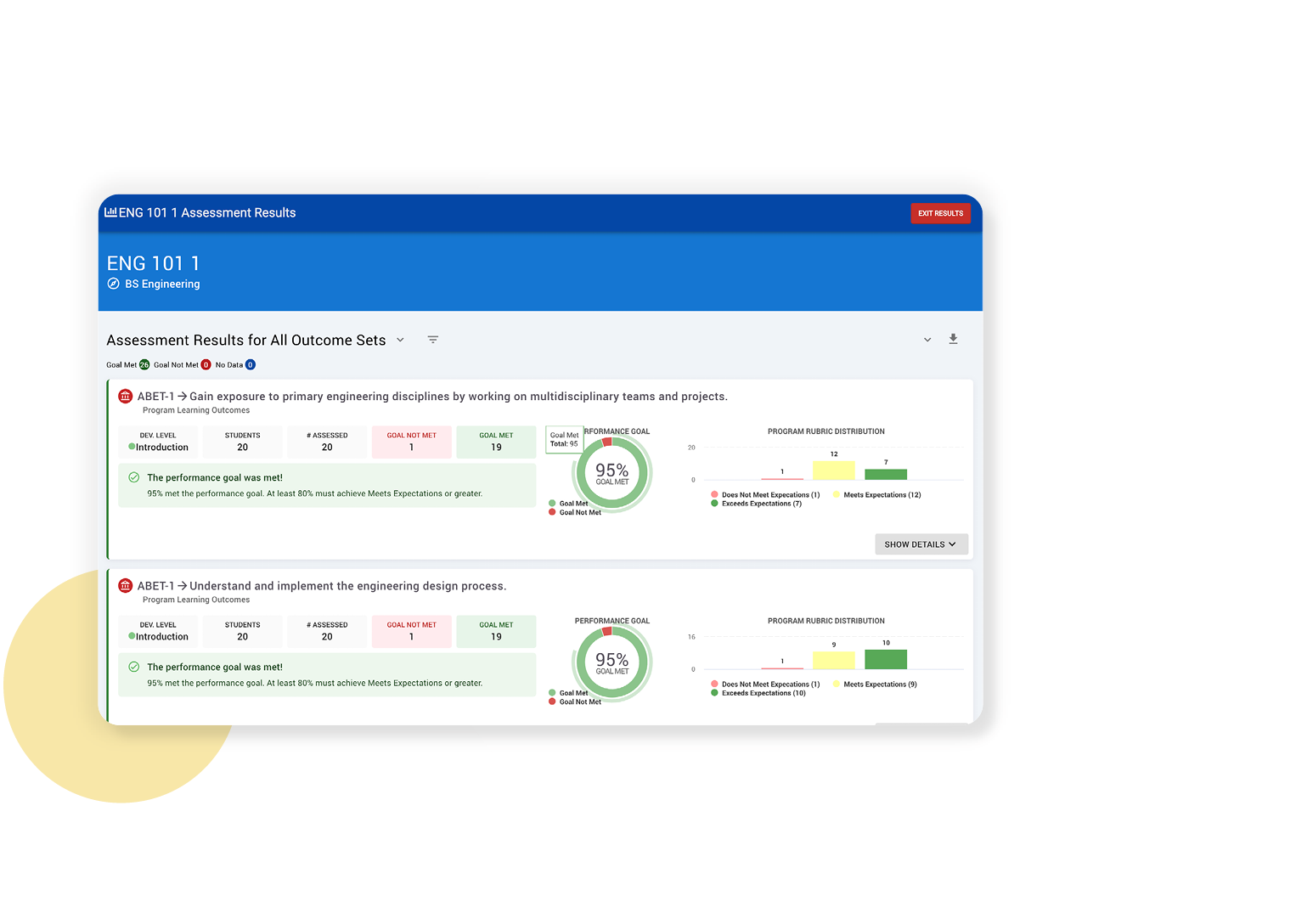

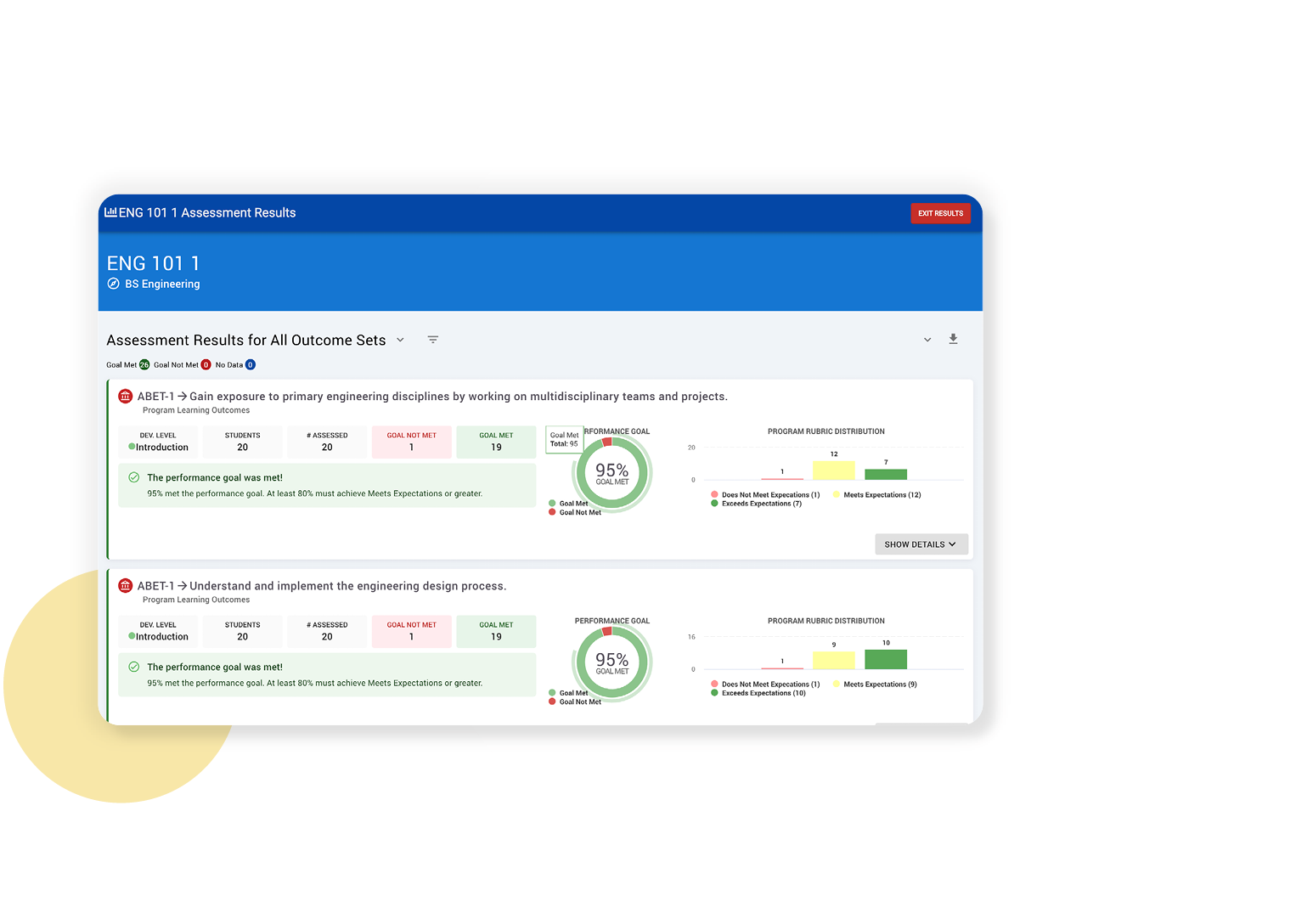

Assessment and Credentialing

Assess student learning outcomes in real-time with a unified platform that empowers you to seamlessly access assessment data and leverage it for accreditation, planning, and continuous improvement. Our technology gives stakeholders - from students to faculty and administrators - fast access to the data and evidence they need across courses, programs, and outcomes.

Explore Assessment and Credentialing

Transformation takes more than technology

Through the discipline of Institutional Performance Management, HelioCampus enables you to connect the dots across academic programming, administrative operations, and student learning outcomes to power integrated planning and continuous improvement.

Making an impact with our clients

Working in higher education today requires leaders to navigate growing pressures in new ways. Hear how our clients and leadership team are thinking about this critical moment through the lens of Institutional Performance Management.

Powering insights for higher education at forward-thinking institutions

Explore our resources

Check out the blog for ideas and best practices to enhance your data analytics, financial intelligence, and assessment efforts.

How to Align Outcomes and Build a Robust Assessment Plan in Higher Education

Student success goes beyond traditional teaching practices. It requires a systematic approach to designing assessment plans, aligning learning outcomes and engaging faculty...

AI-Driven Enhancements in HelioCampus Assessment & Credentialing

As part of our AI strategy, we’re expanding automation and data analysis capabilities in our Assessment & Credentialing products. These updates will simplify how institutions...

How Semantic Layers & Prompt Engineering Empower AI Data

Marley was dead to begin with. It's a great opening line and not just because it instantly draws you in, but it's important to the story. If we don't keep in mind the fact...

Bring insights to life and grow sustainably

See how HelioCampus can enhance your data analytics, financial intelligence, and institutional assessment capabilities.